Could there be some simple ways to reduce dementia risk? The answer is yes.

As the number of older people increases worldwide, so unfortunately does the number of people suffering from Alzheimer’s and other dementias. Based on current trends, the number of individuals with dementia is expected to nearly double every 20 years, with nearly 60% of those affected living in low and middle income nations. By 2050, dementia could affect over 130 million people worldwide and could become a trillion dollar disease by the end of this decade.

A great deal of funding has been invested in developing medications that could prevent the progress of neurodegenerative diseases, but this is proving more difficult than first thought since these diseases are so complex and depend on a multitude of factors. But are there some simple ways to reduce cognitive decline in older people?

Miia Kivipelto, professor at the Department of Neurobiology, Care Sciences and Society of the Karolinska Institutet in Sweden certainly thinks so. Kivipelto is also an AXA research fellow and one of the researchers to have authored the recentLancet Neurologyreport“Defeating Alzheimer’s diseases and other dementias: a priority of European science and society”. She and her colleagues are developing models to assess a person’s risk for developing dementia, which mechanisms drive the disease and how these can perhaps be mitigated through a range of simple measures such as changes in lifestyle. Such changes include a healthier diet (to normalize blood pressure and blood lipids, for example), physical exercise and mental training.

PUTTING THE FINGER ON IMPORTANT RISK FACTORS FOR LATE-ONSET DEMENTIA

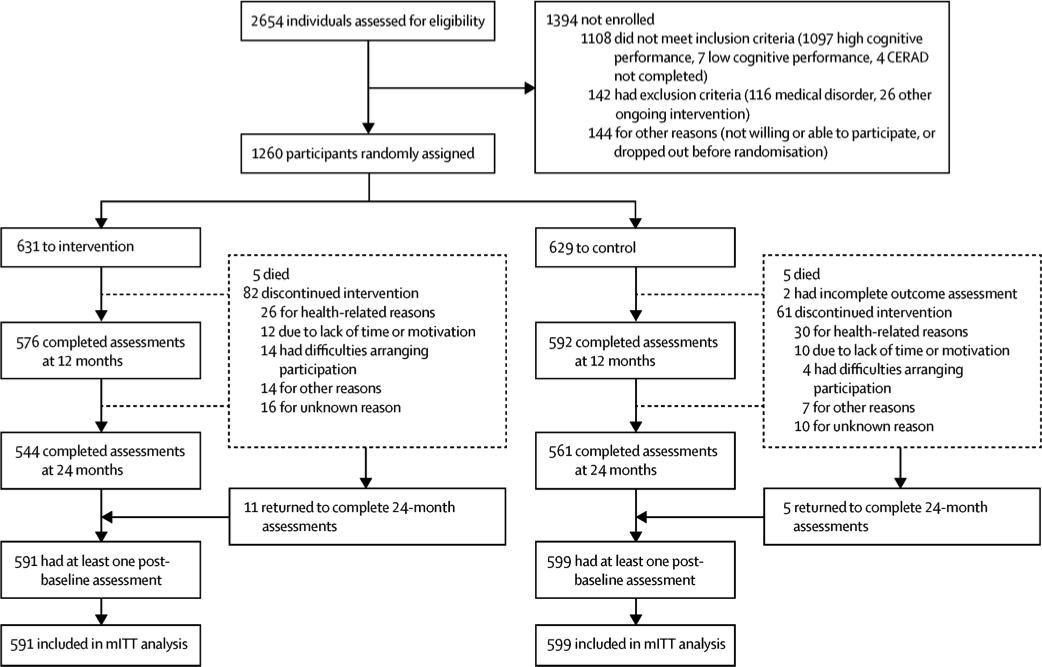

Kivipelto led the Finnish Geriatric Intervention Study to Prevent Cognitive Impairment and Disability(FINGER), which assessed the effects of some of the most important risk factors for late-onset dementia (such as high body mass index, BMI, and cardiovascular health) on how the brain functions. FINGER was the first ever large multi-domain randomized controlled trial of its kind in the world and we assessed several risk factors simultaneously to determine the optimal preventive effect, explains Kivipelto. We studied 1260 individuals from across Finland aged 60-77 over a period of two years. Half of these individuals were randomly allocated to an active study group and the other half to a control group.

All of the study participants were judged to be at increased risk of dementia, that is, they scored more than 6 on the Dementia Risk Score and had a cognition level that was equal to or slightly lower than the mean expected for their age.

CERAD=Consortium to Establish a Registry for Alzheimer’s Disease. mITT=modified intention-to-treat.Credit:The Lancet.

HEALTHY EATING

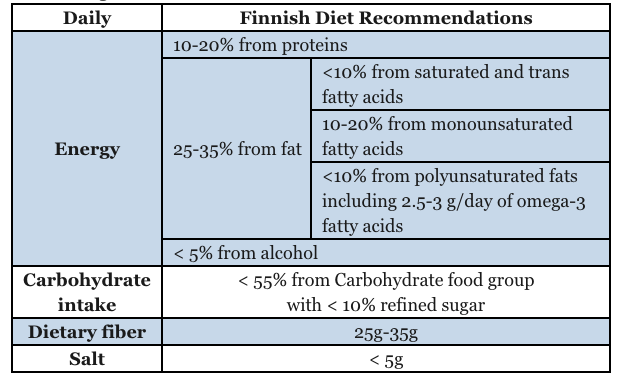

The control group only received “regular” health advice while the active study group benefited from a comprehensive program of healthy eating, muscular and cardiovascular training and brain training exercises. For example, healthy eating advice was based on the Finnish Nutrition Recommendations (which are happily very similar to the Mediterranean diet) - see table

If participants were deemed to be overweight at the start of the study, they were advised to lose between 5 and 10% of their body weight by reducing the number of calories they consumed. All subjects were also told to eat lots of fruit and vegetables and chose wholegrain cereal products over refined ones, low-fat milk and meat products. They were also advised to limit their sugar intake to no more than 50g/day and use vegetable margarine and rapeseed oil instead of butter. Fish was to be consumed at least twice a week.

Table: Testing the Finnish Diet

PHYSICAL AND MENTAL EXERCISE

As for physical exercise, participants followed a modified version of the Dose Responses to Exercise Training (DRs EXTRA) regime (another large randomized controlled trial in Finland that focused on the effects of exercise) and were monitored by physiotherapists in the gym. The exercise included progressive muscle strength training (1-3 times a week) and aerobic exercise (2-5 times a week). The strength training exercise focused on the main muscle groups (knee, abdomen and back, upper back and arm muscles and lower extremity muscles).

Cognitive exercises, led by psychologists, focused on addressing age-related intellectual changes - that is, memory and reasoning applied to everyday activities. Individual sessions included computer-based training at home or at a study site, conducted in two periods of six months with each period comprising 72 training sessions (three times a week with each session lasting around a quarter of an hour). “Executive” functioning (how the brain organizes and regulates thought processes) was also assessed and tests here included mathematical and verbal, working memory (maintenance tasks), episodic memory (relational and spatial tasks) and mental speed (participants were asked to match shapes, for instance).

Kiitos=Thank you!Credit: National Institue for Health and Welfare (THL)

THE MAIN RESULTS

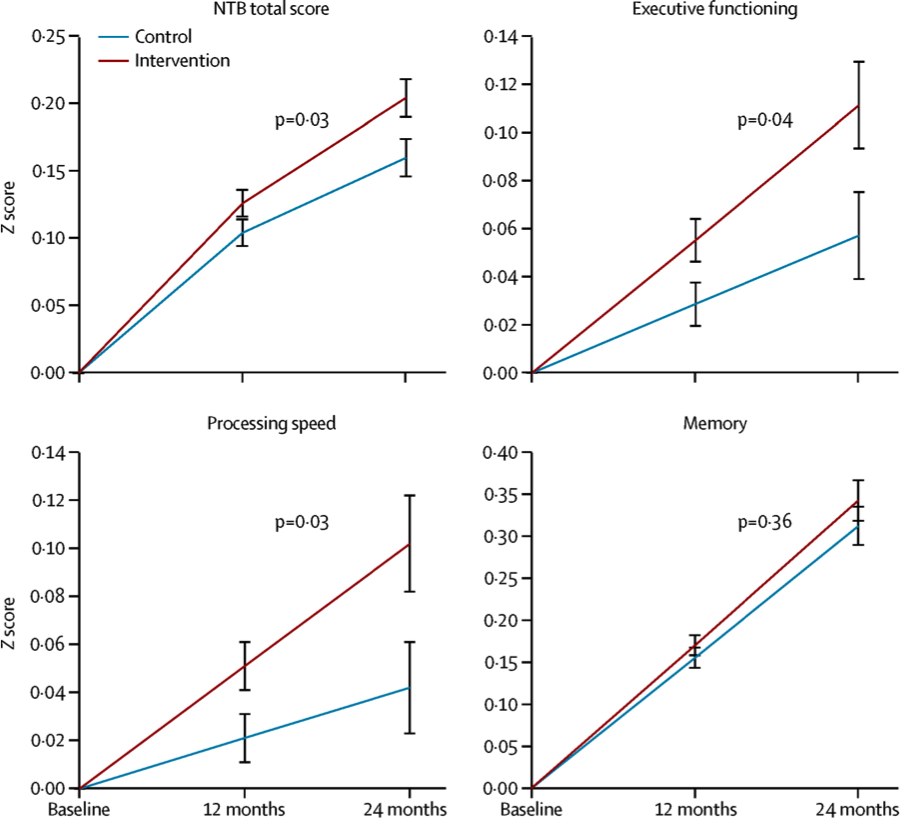

Doctors, nurses and other health professionals met regularly with the study participants over the two years. At the end of this period, their mental abilities were measured using the Neuropsychological Test Battery – a standard test for testing various cognitive domains. Their blood pressure, weight and BMI, and hip and waist circumferences were also measured.

Overall test scores showed an impressive 25% higher improvement in global cognition as compared to the control one, report the researchers, and for some parts of the test, the difference was even more dramatic. For example, executive functioning scores were a staggering 83% higher for the intervention group and thought processing speed was 150% higher. The researchers also saw improvements in participants’ blood pressure and BMI.

The figure shows estimated mean change in cognitive performance from start (or baseline) until 12 and 24 months (higher scores suggest better performance) in the participant population. NTB=neuropsychiatric test battery.Credit:The Lancet

RISK FACTORS ARE DIFFERENT IN MIDLIFE AND OLDER AGE GROUPS

Carol Brayne of Cambridge Neuroscience at the University of Cambridge in the UK, who was not involved in these studies, says that quite a few of the risk factors for developing dementia appear to be most important in midlife, with changing patterns of risk as people enter the older age groups. “Modeling studies, which attempt to analyze the top risk factors and their interrelationship suggest that 30% of clinically diagnosed Alzheimer’s disease could be accounted for by the top seven risks that recently emerged from a large systematic review. We also have empirical evidence that the prevalence and incidence is decreasing in some age groups in certain countries, but the reasons for this decrease have not yet been directly explained by research. The only way to test at what life stage and in what way risk and protective measures are important for developing (or not developing) dementia is to bite the bullet and have a go at trials.

“These trials might be individualized traditional trials as in Kivipelto’s group’s work, or they could be whole populations/communities looking at changing the behavioral environment. Trials in later life, like the ones described in this article, can be done within reasonable timeframes and can look at proximal risk profiles and then dementia progression with a little longer follow-up. A range of experimental designs is needed and Kivipelto and colleagues, along with those in the European Consortium for Prevention of Dementia, have been pioneers here. It is not easy: the studies can be criticized, and their findings challenging to fully interpret (as there are still relatively few yet), but they are really important for the future.

I would also like to add that the differences across generations in some countries' patterns of dementia might also be related to earlier life investment in factors such as maternal health, improved nutrition and health care throughout early life in combination with increased educational levels. These factors are much more difficult to research and we have to look for comparison across geography, time and cultures to see how we can get a handle on these.”

Michael Valenzuela of the Regenerative Neuroscience Group at the Brain & Mind Centre & Sydney Medical School adds: “The FINGER trial was important because it showed that lifestyle modifications can, in principle, slow the rate of cognitive decline in those at risk for dementia. However, that is not the same as preventing or delaying dementia, and longer term follow up and results from other trials will help clarify this key issue. Interestingly, FINGER outcomes were much weaker than anticipated from studies of individual lifestyle interventions, and so it also begs questions about how to best combine different lifestyle interventions in a way that harnesses their benefits."

GOING FURTHER

Kivipelto and colleagues, who reported on their FINGER study in The Lancet, are now following up the participants (and will do so for at least another six years) to see whether reduced cognitive decline actually leads to fewer of the participants being diagnosed with dementia and Alzheimer’s. They say that they are also looking into the various mechanisms behind the observed improvements in brain function.

The researchers have also developed the first dementia risk App based on the results of a previous study known as CAIDE (Cardiovascular Risk Factors, Aging, and Incidence of Dementia). The App, which calculates the risk of getting dementia within the next 20 years based on a person’s weight, cholesterol level, blood pressure, physical activity and years of education, can be downloaded for free for use on an iPhone or iPad. It comes in two versions: one for physicians and one for individuals. It is available in five languages: German, French, Spanish, Russian, and English as default. Other languages will be available soon.

“The biggest risk factor for developing dementia is advanced age. Large epidemiological studies have demonstrated that what is good for the heart is good for the brain,” says Kivipelto. “In other words a healthy lifestyle with physical activity, low blood cholesterol levels, not being obese, and having normal blood pressure at midlife protect not only against cardiac disease, but also against dementia.”

AWARDS FOR MIIA KIVIPELTO

Kivipelto has received numerous prestigious awards, including the Waijlit and Eric Forsgren’s award for outstanding dementia research (2015), Best PI at KI award in collaboration with Nature (2014) and the AXA Research Award (2014). In 2016 she received the Alzheimerfonden’s award for excellent research.

Source : Scientific American

Other articles from the same author

Discover research projects related to the topic

Mental Health & Neurology

Extreme Weather Events

Pollution

Alzheimer's Disease, Dementia & Neurodegenerative Diseases

Droughts & Heatwaves

Air Quality

Mécénat des Mutuelle

France

CLIMABRAIN: Impacts of Extreme Weather on the Most Vulnerable Living with Alzheimer's disease

In the context of the increase in extreme weather events due to climate change, the project led by Tarik Benmarhnia... Read more

Tarik

BENMARHNIA