Climate Change

Economics & Global Development

Finance, Investment & Risk Management

Greenhouse Gases Emissions

Trade, Consumption & Global Markets

Climate Adaptation & Resilience

Political Economy & Governance

Ph.D

Germany

2012.02.29

Carbon tariffs: an instrument for tackling climate change?

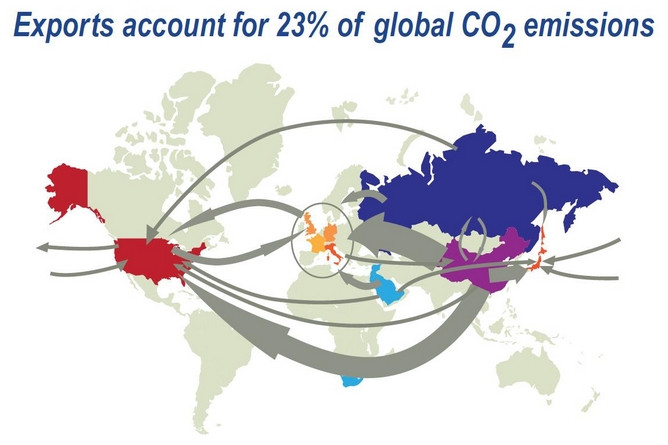

However, almost a quarter of China’s CO2 emissions come from its exports. So China and other nations view carbon tariffs as trade sanctions and protectionism. They even threatened to start a “trade war” if such schemes were to be put into place. They stress the role that carbon emissions have played in the industrialization of advanced economies and demand increased financial aid in order to reduce their emissions.

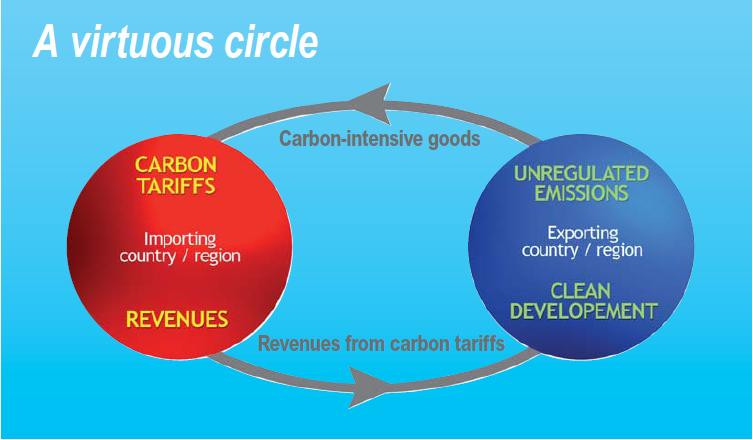

To avoid this coming carbon war, Springmann proposes to recycle the tax revenues from carbon tariffs (claimed in the importing country) to the exporting country as investments in climate change mitigation and adaptation measures. This coupled scheme addresses the concerns about competitiveness and reducing emissions in one part of the world and economic progress in the other. Since it acknowledges the demand for imports as an emissions-causing factor, it may therefore represent a consensus solution within a global climate policy. According to Springmann, a preliminary assessment has indicated that the revenue from this scheme would range between $8 and $50 billion per year, depending on the price of carbon. In comparison, at the climate summit in Copenhagen in 2009, it was agreed to create a “Fast Start Fund” to support climate adaptation and clean technology in developing countries. The pledged contribution is $30 billion over the next three years. Carbon tariffs would add significant revenue streams to this effort.

My research focuses on the division and quantitative analysis of climate policies. In particular, I propose to couple carbon border tariffs with clean development funding in the exporting country or region. This research project follows a consumption-based approach to carbon emissions to enable a consensus between developing and developed nations. The proposed policy combination is to be assessed on the global, national and regional level with respect to streams of clean development funding and potential carbon emissions reductions. The national and regional case studies are focused on China as the world’s top emitter of carbon dioxide, major trade nation and greatest critic of carbon tariffs.

Carbon Tariffs: Another Name for Green Protectionism?

Carbon tariffs to finance clean development

Marco Springmann, AXA PhD Fellow

German Institute of Economic Research (DIW), Berlin

Marco Springmann is a physicist turned economist. He completed a first Master’s degree at Stony Brook University (United States) with research focused on atmospheric process modelling. He then went on to obtain a second Master’s degree in Ecological Economics at the University of Leeds (United Kingdom). “The fundamental science of climate change is well established and the scientific community has been urging society to act. Now the real issues are economic and political hurdles”, he says. To overcome some of those hurdles, carbon tariffs, a tax on carbon-intensive imports, have been proposed, which triggered heated international debates over the past few years. They are at the centre of the young scientist’s doctoral research project, scheduled to start this year at the German Institute of Economic Research in Berlin.

Do we need another form of tax, such as carbon tariffs?

Right now, the answer to this question depends on whom you are asking. The industrialised countries, in particular France and Italy, have been advocating to adopt carbon tariffs on products imported from developing countries, such as China. The main reason is that the European Union member states and other rich nations have implemented binding greenhouse gas emissions reduction targets (in particular on carbon dioxide), while poorer countries have so far resisted legal commitments. Emissions reduction target explicitly or implicitly give carbon a price.

In the European Union, the price of carbon is set in a market-based approach through an emissions trading scheme, in which total carbon dioxide emissions are capped at specific reduction levels and companies can buy or sell emission permits. However, similar economic measures are lacking in developing countries. Therefore, they can produce cheaper carbon-intensive goods. Promoters of carbon tariffs think that taxing those goods at the border will account for this difference in price and indirectly regulate the associated emissions. The rationale is to compensate the competitive disadvantages of domestic products and to prevent the move of domestic industries to unregulated countries.

What are the political hurdles to carbon tariffs ?

Almost a quarter of China’s CO2 emissions comes from its exports (see Figure 1). So China and other nations view carbon tariffs as trade sanctions and protectionism. They even threatened to start a ‘trade war’ if such schemes were put into place. They stress the role carbon emissions have played in the industrialisation of advanced economies and demand increased financial aid in order to reduce their emissions.

How does your research address this dispute?

I propose to use carbon tariffs for clean development funding. My idea is to recycle the tax revenues from carbon tariffs (claimed in the importing country) to the exporting country as investments in climate change mitigation and adaptation measures there (see Figure 2). This coupled scheme addresses the concerns of competitiveness and emissions reductions in one part of the world and of economic progress in the other. It may therefore represent a consensus solution within a global climate policy.

It is also a novel, consumption-based approach which acknowledges the demand for imports as emissions-causing factor. How popular is that view ?

Since 2007, increasing attention has been centred on consumers’ responsabilities, helped by methological advances in calculating those. This can result in substantial changes in emissions allocations. For example, Germany is now considered to be in line with its obligations under the Kyoto Protocol, but its national allocation doesn’t include the goods from abroad (including their embodied emissions) which are purchased by German citizens. If you count those in, the emissions in Germany are very unlikely to have decreased to the same proportion. This same argument holds true for the United Kingdom. More generally, if you don’t account for emissions embodied in trade, some countries may have stringent policies, but global emissions could keep on rising. This also means that there is a potential for educating people in sustainable purchasing. We know that behavioural changes can make a great difference in reducing greenhouse gas emissions, sometimes more than technological advances and energy saving measures.

How much revenue could be raised from your proposed scheme?

A preliminary assessment indicates that the revenues would range between 8 to 50 billion dollars per year, depending on the price of carbon. (The current price in the European emissions trading scheme is approximately 10 dollars per tonne of CO2 equivalent, but it could rise to 60 dollars per tonne if carbon was priced according to its real cost to society.) In comparison, the estimated funding requirements for climate change adaptation in poor countries range from USD 4 to 109 billion per year. At the climate summit in Copenhagen in 2009, it was agreed to create a “Fast Start Fund” to support climate adaptation and clean technology in developing countries. The pledged contribution is USD 30 billion over the next three years. Carbon tariffs would add significant revenue streams to this effort.

What will your doctoral research precisely focus on ?

I plan to further substantiate those results and analyse in more detail what carbon emissions reduction could be achievable globally, as well as on national and regional levels. I will particularly study the effect on China, to see whether its opposition to carbon tariffs would also be justified in my coupled scheme.

To add or modify information on this page, please contact us at the following address: community.research@axa.com

Marco

SPRINGMANN

Institution

University of Oldenburg

Country

Germany

Nationality

German

Related articles

Climate Change

Finance, Investment & Risk Management

Societal Challenges

Climate Adaptation & Resilience

Insurance & Risk Management

Environmental Justice

Civil Society & Governance

AXA Project

Italy

AXA Research Lab on Climate Change, Risk and Justice

In response to three research questions: How can the private and financial sectors contribute to a just transition to a... Read more

Gianfranco

PELLEGRINO